From his earliest forays into the world of visual art, Jordan Kantor has inextricably linked art-making and art history. This dual interest has led Kantor down a path of academic rigor, curatorial studies, art teaching, and art writing–all of which informs Kantor’s strongest passion: being an artist. While still in high school, he started taking art history courses at the local university (Princeton). From there, Kantor went on earn a degree in painting at Stanford, where he developed, as a thesis project, an exhibition of prints by Albrecht Durer: “It was not so much a scholarly thing,” explains Kantor, “but more from a practical perspective, of my own interest in reproductive mediums, narratives, across a certain set of artworks.”

Kantor later pitched the thesis exhibition to Harvard, which led to a three-year curatorial project, and to Kantor earning his PhD there, in the history of art and architecture. Meanwhile, he also began to build a name for himself as an artist, having shows in New York, where he was living. “One of my goals was to get out of the studio and not just be in my own head,” he explains. “I was introduced to some people at Artforum magazine, and I decided I wanted to write reviews, in the tradition of artists who wrote, such as Donald Judd–who found a way to work out problems in their artistic practice through a writing practice.” He began writing regularly for Artforum, and to this day continues to publish articles on contemporary art. Kantor also further engaged in curatorial pursuits, working for two years as an assistant curator at MOMA. But his primary interest remained art making, so when the opportunity arose to move to San Francisco to teach at CCA and return to a full-time studio practice, Kantor made the move.

Over the last decade, Kantor has focused on creating work that layers art-historical references, among them works such as Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergere, and Monet’s Les Mueles, for instance; and reproduction, be it photography, digital Internet imagery, or X-rays; along with various stylistic allusions, from the minimalist grid and monochromatic color to the pared-down approach of Luc Tuymans, mixing them all together with an acute awareness of the object-hood of art. In recognition of his practice, in 2008, he received a SECA award from SFMOMA and was included in the 2008 California Biennial, at OCMA.

Given the vast and multifaceted background Kantor pulls from, the resulting body of work may appear incongruous to an unsuspecting viewer. “You might walk into a show of mine,” Kantor states, “and it might look like a group show, with works with so many different approaches and aesthetics. That’s because the unitary element of my practice isn’t aesthetics, it’s concepts.” One consequence of his art being so steeped in concept and the art world dialogue is that the work, by Kantor’s own admission, has required some background knowledge to be fully understood and appreciated. This is something the artist is veering away from in his current work, which explores the artistic value of materials and objects surrounding the art-making process; can, for instance, the rags used to wipe his paintings be configured into artwork in their own right?

For his recent solo show at Ratio 3 in San Francisco (January 11 through February 9), then, Kantor crafted “a large group, at least ten, of the rag paintings, in four-color, hand-painted artist frames,” he says. Additionally, he crafted “a suite of ten small representational paintings based on photographs of a woman’s hand in front of differently colored monochromatic fabric and a small group of large abstract works painted on wooden lattice.”

“Now the work is what it is,” he explains, “a display of materials. If you want to pick at it, you can tease out the thoughts that come from art history, but I don’t see that as being a prerequisite to having access to my work. It’s an open-ended process. I’m more interested in asking questions than arriving at answers.” This act of creating a dialogue strikes to the heart of what has driven Kantor since the beginning: “I see the whole process of being an artist as a way of engaging in a conversation across time,” he says, “sometimes with historical figures and sometimes with my peers and sometimes with people I don’t even know.”

![Heinwein[SF]](https://artbeatbayarea.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/heinweinsf.jpg?w=300&h=164)

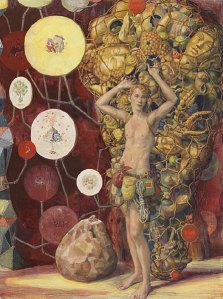

The immediate impression of “EINFLUSS: 8 from Düsseldorf” (on view through February 5, 2011) is, wow, these artists can paint! Save the two works by artist Luka Fineisen, a sculpture and a gestural wall piece, both made with plastics, all of the other twenty-seven, mostly large-scale works in the exhibition are paintings, and there’s something wonderful to be found in every one of them.

The immediate impression of “EINFLUSS: 8 from Düsseldorf” (on view through February 5, 2011) is, wow, these artists can paint! Save the two works by artist Luka Fineisen, a sculpture and a gestural wall piece, both made with plastics, all of the other twenty-seven, mostly large-scale works in the exhibition are paintings, and there’s something wonderful to be found in every one of them.